I am rereading St. Francis de Sales’s

Treatise on the Love of God (which, by the way, I recommend to anyone

who has or can muster a tolerance for flowery language). The

circumstances of my first reading are somewhat shrouded by the mists of time,

but I think it must have been about the period when I started graduate school.

No, it hasn’t been that long; it

just feels that way.

Graduate school certainly has had

its effect, however; for the preface and first chapter, which I remember

finding a bit dull, proved “quite the opposite, in fact.” The more you

know, the more you catch. This time, two things struck me, both on a

purely secular level, but both having perhaps spiritual morals (if I may so

speak).

The first was the following

passage:

Soon

afterwards his Highness came over the mountains, and finding the bailiwicks of

Chablais, Gaillard and Ternier, which are in the environs of Geneva, well

disposed to receive the Catholic faith which had been banished thence by force

of wars and revolts about seventy years before, he resolved to re-establish the

exercise thereof in all the parishes, and to abolish that of heresy, and whereas

on the one side there were many obstacles to this great blessing from those

considerations which are called reasons of State, and on the other side some

persons as yet not well instructed in the truth made resistance against this so

much-desired establishment, his Highness surmounted the first difficulty by the

invincible constancy of his zeal for the Catholic religion, and the second by an

extraordinary gentleness and prudence. For he had the chief and most obstinate

called together ,and made a speech unto them with so lovingly persuasive an

eloquence that almost all, vanquished by the sweet violence of his fatherly

love towards them, cast the weapons of their obstinacy at his feet, and their

souls into the hands of Holy Church.

And

allow me, my dear readers I pray you, to say this word in passing. One may

praise many rich actions of this great Prince, in which I see the proof of his

valour and military knowledge, which with just cause is admired through all

Europe. But for my part I cannot sufficiently extol the establishment of

the Catholic religion

in these three

bailiwicks which I

have just mentioned, having seen

in it so

many marks of

piety, united with

so many and

various acts of

prudence, constancy, magnanimity, justice and mildness, that I seemed to

see in this one little trait, as in a miniature, all that is praised in princes

who have in times past with most fervour striven to advance the glory of God

and the Church. The stage was small, but the action great. And as that ancient craftsman

was never so much esteemed for his great pieces as he was admired for making a

ship of ivory fitted with all its gear, in so tiny a volume that the wings of a

bee covered all, so I esteem more that which this great Prince did at that time

in this small corner of his dominions, than many more brilliant actions which

others extol to the heavens.

It’s a beautiful bit of prose, and

a lovely little tribute to … well, if I’ve got my dates right, King Henry of

Navarre. Yes, that’s right: the dude who

was reviled in England for becoming Catholic when he ascended (in order to ascend?)

the throne of France, reportedly observing that Paris was “worth a Mass.” (Talk about Machiavellian ragione di state!) He also, of course, in his younger Huguenot

days, narrowly escaped the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. As Catholic king, he extended toleration to

Protestants and (wait for it) was assassinated by a fanatical Catholic. Apparently some people called him “Good King

Henry.” Who knew? St. Francis, at any rate, seems to have

thought his conversion sincere. And no: it

probably wasn’t royal boot-licking on St. Francis’s part, because Henry had

been assassinated six years earlier, in 1610.

(The Treatise was published in

1616, the year of Shakespeare’s death.)

In any case, St. Francis notes his

previous tendency, “while I was not yet bishop, having more leisure and less

fears for my

writings,” to dedicate his works “ to

princes of the

earth,” avowing a new intention:

but now

being weighed down with my charge, and having a thousand difficulties in

writing, I consecrate all to the princes of heaven, that they may obtain for me

the light requisite, and that if such be the Divine will, these my writings may

be fruitful and profitable to many.

There’s the Renaissance for you:

patronage, independence, and the reformation of one’s life in a few short

paragraphs.

The second thing I noticed was the

way in which the first chapter rung changes on common themes in Renaissance

culture: paradox, order, the macrocosm/microcosm, beauty as a telos … To make a comparison for modern

readers: It would be like a priest today mounting the pulpit to deliver an

opening salvo dealing with Minimalism and Karma. St. Francis is trendy, in a

sixteenth-century sort of way.

Since it’s Sunday, and you may be

in want of a good sermon, I’ll just leave that complete first chapter right

here.

CHAPTER I.

“That for the Beauty of

Human Nature God Has Given the Government of

All the Faculties of the Soul

to the Will.”

Union in distinction

makes order; order

produces agreement; and

proportion and agreement,

incomplete and finished things, make beauty. An army has beauty when it

is composed of parts so ranged in order that their distinction is reduced to

that proportion which they ought to have together for the making of one single

army. For music to be beautiful, the voices must not only be true, clear, and

distinct from one another, but also united together in such a way that there

may arise a just consonance and harmony which is not unfitly termed a

discordant harmony or rather harmonious discord.

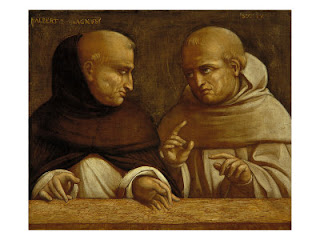

Now as the angelic S. Thomas, following the great S.

Denis, says excellently well, beauty and goodness though in some things they

agree, yet still are not one and the same thing: for good is that which pleases

the appetite and will, beauty that which pleases the understanding or

knowledge; or, in other words, good is that which gives pleasure when we enjoy

it, beauty that which gives pleasure when we know it. For which cause in proper

speech we only attribute corporal beauty to the

objects of those

two senses which

are the most

intellectual and most

in the service

of the understanding—namely, sight

and hearing, so

that we do

not say, these

are beautiful odours

or beautiful tastes: but we rightly say, these are beautiful voices and

beautiful colours.

The beautiful then being called beautiful, because

the knowledge thereof gives pleasure, it is requisite that besides the union

and the distinction, the integrity, the order, and the agreement of its parts,

there should be also splendour and brightness that it may be knowable and

visible. Voices to be beautiful must be clear and true; discourses

intelligible; colours brilliant and shining. Obscurity, shade and darkness are

ugly and disfigure all things, because in them nothing is knowable, neither order,

distinction, union nor agreement; which caused S. Denis to say, that “God as

the sovereign beauty is author of the beautiful harmony, beautiful lustre and

good grace which is found in all things, making the distribution and

decomposition of his one ray of beauty spread out, as light, to make all things

beautiful,” willing that to compose beauty there should be agreement, clearness

and good grace.

Certainly, Theotimus, beauty is without effect,

unprofitable and dead, if light and splendour do not make it lively and

effective, whence we term colours lively when they have light and lustre.

But as to animated and living things their beauty is

not complete without good grace, which, besides

the agreement of

perfect parts which

makes beauty, adds

the harmony of

movements, gestures and actions, which is as it were the life and soul

of the beauty of living things. Thus, in the sovereign beauty of our God, we

acknowledge union, yea, unity of essence in the distinction of persons, with an

infinite glory, together with an incomprehensible harmony of all perfections of

actions and motions, sovereignly comprised, and as one would say excellently joined

and adjusted, in the most unique and simple perfection of the pure divine act,

which is God Himself, immutable and invariable, as elsewhere we shall show. God,

therefore, having a will to make all things good and beautiful, reduced the

multitude and distinction of the same to a perfect unity, and, as man would

say, brought them all under a monarchy, making a subordination of one thing to

another and of all things to himself the sovereign Monarch. He reduces all our

members into one body under one head, of many persons he forms a family, of many

families a town, of many towns a province, of many provinces a kingdom, putting

the whole kingdom under the government of one sole king. So, Theotimus, over

the innumerable multitude and variety of actions, motions, feelings,

inclinations, habits, passions, faculties and powers which are in man, God has

established a natural monarchy in the will, which rules and commands all that is

found in this little world: and God seems to have said to the will as Pharao

said to Joseph: Thou shalt be over my house, and at the commandment of thy

mouth all the people shall obey. This dominion of the will is exercised indeed

in very various ways.